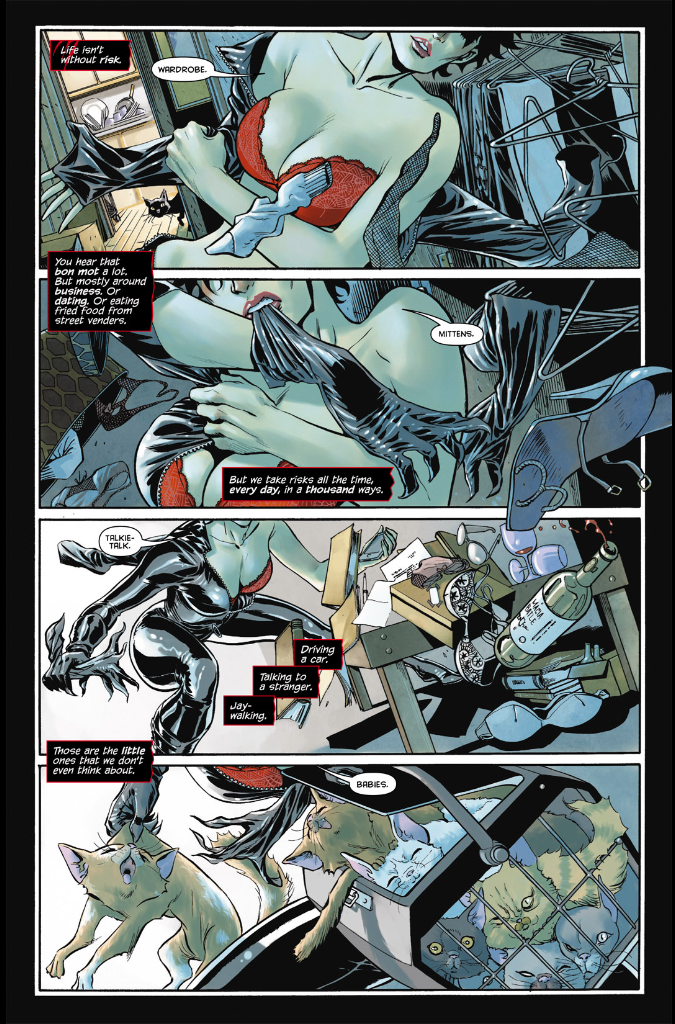

And in case that didn't get the blood flowing appropriately, here's page 1:

This, gentlemen, is why women don't talk to us. Or, put another way, it's why we're not perceived as being able to talk to women. After all, how do you talk to a person when this is the way you picture them? More of an immediate problem for the comics medium: how do you write them?

Writing female characters can be hard for many male writers. Outside of any hangups they may have with women, it's daunting to write for someone from a different background. Be it gender or race or creed, writing for someone else presents pitfalls and challenges that can drive a lesser writer mad. But it's what all writers sometimes have to do. Not being able to empathize with your subject is a one way ticket to shitty writing. And it will show through. You could try and write only from perspectives similar to your own, but that quickly limits your storytelling possibilities. And people start to notice.

People notice a lot quicker in visual mediums, like comics. The eye will catch and process artwork a lot quicker than it might with large chunks of prose, which have to be parsed and balanced against concepts like irony and satire. A book set in the 19th Century will have a very different context for the lives and attitudes of female characters than will a book set in the early 21st Century. In a visual medium, however, the context is out in the open and, usually, unmistakable. Someone with no familiarity with the book in question, or any of the work of the writer or the artist (if they're separate people), or the characters, or even the medium as a whole, can pick up that book and and experience the purest visceral experience that those images--or even a single image--instills in them.

Some argue that male characters are often drawn to the same absurd, impossible proportions that women are. This is true. Larger than life fantasy characters tend to be envisioned as, well, larger than life fantasy characters. But this is also not the point. When male superheros are posing something like this:

...we'll have an egalitarian industry. And a more consistently stupid one. Some brilliant person drew this chart, featuring the male members of the Justice League in the exact same pose as Wonder Woman had been depicted in one of the promo sheets for the New 52:

That last image, if you're wondering, is of the Wonder Woman redesign, her relatively-recently added pants exchanged for the "classic" or "canon" panties she'd long worn. This change followed an uproar on the part of the fanboys. If you're not beginning to see the problem, maybe Namor (the Sub-Mariner!) can convince you?

I'm going to give some rare props to Marvel Comics: that is some fantastic egalitarianism. However, this particular image did not appear in any of the comics but in a one-off Marvel swimsuit calendar (yes, that happened). So it's probably not fair to consider it on the same level. Still, you can imagine the state of the industry today if more of the male superheroes looked more like Namor (the Sub-Mariner!) does here. And you'd of course have to imagine a near total reversal of the real world gender relations of the last century in order to allow for this sort of thing.

And as women in the real world have assumed more high profile public and private roles outside the home and generally become less, you know, second class citizens, women in comic books have responded by becoming ninja-like ass-kickers of the same semi-decent character development as their male counterparts, albeit with considerably more sex appeal. Many are still the damsel in distress (Lois Lane, even with less focus on her need to marry Superman, remains, all too often, fodder for villain capture--a hack adventure writer's best tool even outside of the sexism). Still others exist solely to exhibit that particular style of pseudo-feminism known as waif-fu. And all of them, all of them, eventually establish a relationship with a major male character because any time you have a never-ending series, constantly demanding new story material, you run the risk of slipping into soap opera territory. And of DC's New 52 books, less than a dozen star female characters or feature female characters as a central part of a group, ala Wonder Woman in Justice League.

There is another argument for this sexual depiction of woman that I feel I must address. It goes something like this: in these universes of thousands of characters, some women are naturally going to be more sexual. After all, it makes sense that Emma Frost would walk around in her underwear most of the day: if you're focused on her body, you're less likely to notice her rifling through your head with her telepathy (though it begs the question: are gay men and straight women immune?). On the more consistently villainous side of things, Poison Ivy dresses like this to enhance her hypnotic appeal, earning her yet more male slaves to do her bidding. In her own way, Ivy is a reflection of the comics industry's hold on men for illicit gains and I've long wanted to see a more aware and ambitious writer tackle that head on. This apparent need for sexualization, however, does not seem to hold for the male characters. Well, aside from Namor (the Sub-Mariner!) up there.

And how do you explain this significant tilt toward the extreme end of the sexual spectrum? Why don't comic book women run the gamut, from hyper-sexual, to casually sexual, to sometimes sexual, to asexual as real women do and good characters would? There's lazy writing and derivative artistry, yes. There's also the economic need to sell monthly books to the same people who've always bought them, a group of people usually perceived as being sex-starved teenagers. That group doesn't help itself when it continues to buy the books month after month, even after they may have long lost interest in whatever the writers are doing; it's habit more than anything. And the nail is pummeled into the coffin when the less imaginative of that group go on to write the characters, mostlyyearning to recreate and revisit the stories and characterizations of their youth. And the only evolution the medium sees is that of one-upsmanship, where every month demands new extremes of over-the-top sex and gritty violence until we get something like the 1990's.

It's not merely the comic book geek image I wish to throw off. I'm more or less at peace with that. It's the fact that a medium that could be one of the most sophisticated and effective in all storytelling is so saddled with sexual iconography that it can't mature beyond early adolescence. When the talent pool will remain permanently shallow, no one from outside will have reason to take it seriously enough to elevate it to the level of art that it can be and the medium can stagnate. The depiction of women is just the most glaring example of where these comics go wrong.

This has gotten a little better. Part of it is that some people--among them prominent female writers--have started getting louder about it. And as more women--like Amanda Conner--become very big names in the industry, we can hope for a sea change. But it's going to require a more concerted effort, treating all of its characters with the same seriousness that we expect of some of the better books and movies and television shows. It can be done. It has been done. It just requires some more serious attempts at solid and interesting writing, the way Scott Snyder is in his current run on Batman and, to a lesser extent, as Brian Azzarello is on Wonder Woman. The world needs more comics with the depth and maturity of Watchmen, not Watchmen prequels. Thirty years after the early breakthrough works of Alan Moore and Frank Miller, it's time to move past the Rob Liefeld's and latter day-Frank Miller's and make good on all those old promises.

Isn't that right, Namor?

No comments:

Post a Comment